Tupperware – Focus on Happy

Son-in-law Mike has caught the family bug. A veteran thrifter, he’s now selling vintage goodies in a little mall north of town – bits of MCM barware, pieces of occasional furniture, lamps, and “anything black and teal.” His own paintings, which vibe perfectly with a 1970s aesthetic, provide a bold backdrop in the booth.

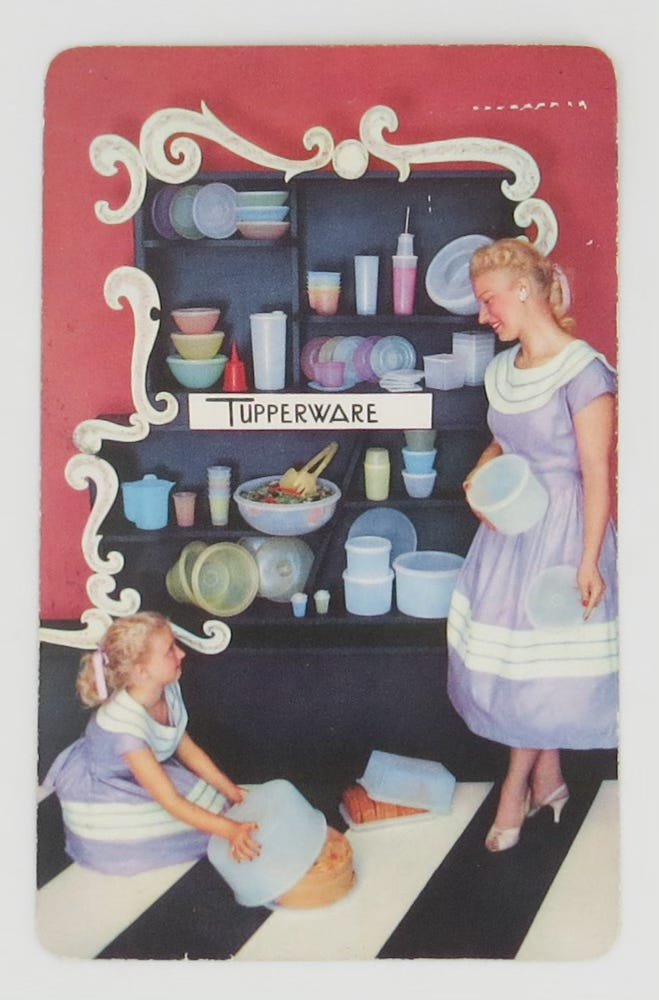

One of Mike’s big sellers is approaching an anniversary: Of the many copyrights for Tupperware food storage containers, one was granted on November 8,1954.

Tupperware?

As someone who grew up with the stuff its popularity among young dealers and collectors is a bit of a mystery. Of course, Mother used Tupperware in her kitchen and when I set up housekeeping I purchased a few pieces, too. It did not occur to us then that we were purchasing a future collectible.

But if we pay heed to Harry Rinker’s mantra that most collectors are trying to buy back their grandmother’s or parent’s furnishings, then collecting Tupperware makes a little bit of sense.

Invented in 1946 by Earl Tupper, a plastics entrepreneur, sales of Tupperware floundered during its first few years. That is, until 1949, when he met Brownie Wise who had developed a unique, fun way to sell other types of merchandize at home parties. Tupper offered Brownie a position managing sales and Tupperware became a household name.

Company lore suggests that housewives made frugal by war rationing needed reliable food storage containers. Tupper’s invention of an airtight lidded bowl promised to eradicate food spoilage.

There was, however, a secondary appeal to Tupperware – or rather its home party sales model. Women who had previously worked in war production factories found themselves pushed out of work by returning soldiers. While women might have willingly left those factory jobs, they sure didn’t want to leave behind the financial independence provided by employment outside the home.

Tupperware offered women opportunities to return to the workforce. An ambitious sales rep could work part-time and maintain a façade of happy homemaker while sometimes earning more than her husband. “In a very nonthreatening way,” Bob Kealing observed in Life of the Party, “the Tupperware phenomenon was changing expectations of what women could achieve. One sale at a time, housewives were finding an economic niche all their own outside the household.”

The company supported its sales force with mentorship, motivational newsletters, and a festive annual convention where tops sellers were recognized with prizes like mink coats and Cadillacs. Justifiably proud of themselves, convention goers shared glowing stories of generating enough income to buy a second car or send their kids off to college. Brownie Wise was ever-present as the doyenne of home sales, cheerleading, teaching, pushing for new product development.

I asked Mike why Tupperware appeals to him. “It’s something I remember from childhood,” he said. “My Mom might have tried to sell Tupperware for a hot second – she tried to sell lots of things like that.”

“With Tupperware, I love that they had specific things to hold salads, lettuce, biscuits. I love the onion and pickle keepers. Those sell really fast.”

Tupperware is oddly appealing. First came the pastel colors of nesting Wonderlier bowls and later offerings of storage bins in 1970s tangerine and apple green -- all designed to twinkle the eye while stretching the budget. The company’s success can be measured, in part, by the ways in which its name is part of the everyday lexicon. Even though we no longer stock our kitchens with the stuff, we all call our Rubbermaid containers ‘Tupperware.’ (Sincere apologies to Ohio’s Rubbermaid corporation!)

Sleek, modern, liberating, Tupperware is included in the Smithsonian Museums, along with Julia Child’s kitchen. A star turn in “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” helped boost its collectability with a short scene mildly lampooning home parties, Midge’s guests all sporting hats made from Wonderlier bowls.

The product’s cultural influence is ubiquitous – just as Tupperware seemed to be in every kitchen back in the 1970s, it was so mainstream poets were inspired to eulogize the burping bowls. In Walt Band’s poem “Tupperware,” the narrator watches a young couple examine kitchen items at an estate sale, their ”joy of fondling Tupperware” reminding him of his wife’s delight with Tupperware purchases 50 years earlier.

As a business concern, Tupperware has experienced ups and downs, expanding into international markets and a few bankruptcy filings here in the states. At present, it is trying to maintain its market share by selling on-line. The Tupperware website claims that “although ownership of the Tupperware brand may have changed, the brand’s legacy continues in its new owners, whose commitment remains firm: to deliver the iconic, high-quality, innovative Tupperware products that consumers trust, while supporting its community of sellers and expanding retail partnerships.”

Not surprisingly, the Tupperware website does not acknowledge the existence of a secondary market for its early products. That seems like a missed opportunity: Today’s entrepreneurs – resellers – keep alive the company’s ideals by introducing Tupperware to a younger generation of collectors who seek mid-century design and practice sustainable housekeeping by making use of yesterday’s plastic.

Mike says he’s doing well enough to keep shopping for his mall booth. “All my stuff is fun – Tupperware is fun. It lets me focus on ‘happy’ – and we all need more of that these days.”

Read more about it: I recommend Bob Kealing’s Life of the Party: The Remarkable Story of How Brownie Wise Built, and Lost, a Tupperware Party Empire. He makes a convincing argument that Tupperware’s huge success would not have been achieved without the “soft feminism” of its female sales force. Deeply researched, well-written, with lots of archival photos to round out the story.