Feed Sack Mystery Begins in Decatur

Among the many feed sacks bought and sold over the years, none have been more intriguing than those with signatures – a designer’s initials or a maker’s mark. The marks usually are tiny and difficult to decipher, so I was intrigued when I came across a sack printed in a lovely toile pattern marked on the selvedge with the name Staley.

My husband, Ed, hails from Decatur, Illinois, headquarters for A.E. Staley Manufacturing, one of the country’s largest producers of soybean and corn products. Dubbed the ‘Castle in the Cornfields,’ Staley’s Art Deco office and plant buildings are visible for miles. Many of Ed’s relatives worked for Staley and we look out for collectibles from the company.

I purchased the Staley feed sack in a box lot at an auction here in central Ohio. In the flurry of bidding, I didn’t pay too much attention to small details – it was later that I discovered the box lot included the sack with the Staley name.

Did A.E. Staley commission these sacks for their grain products?

On our next trip to Decatur, we visited the Decatur Public Library to peruse the local history collection – Ed looking for more information about Great Grandfather Enoch, me to see if anything could be learned about the Staley feed sack. My research began back in the days before digitization, so the librarian sat me down with folios filled with back issues of The Staley Journal, the company newsletter. (Since then, most issues of the newsletter have been digitized; read back issues here: Staley Library.)

Like most industries during World War II, Staley jumped in to support America’s efforts in the European and Pacific theatres of fighting. The Decatur plant was refitted to produce an array of soy and corn products that were used by other industries supplying the troops – making preservatives for k-rations and starch for uniforms and bandages. Even bombs were perfected using Staley products.

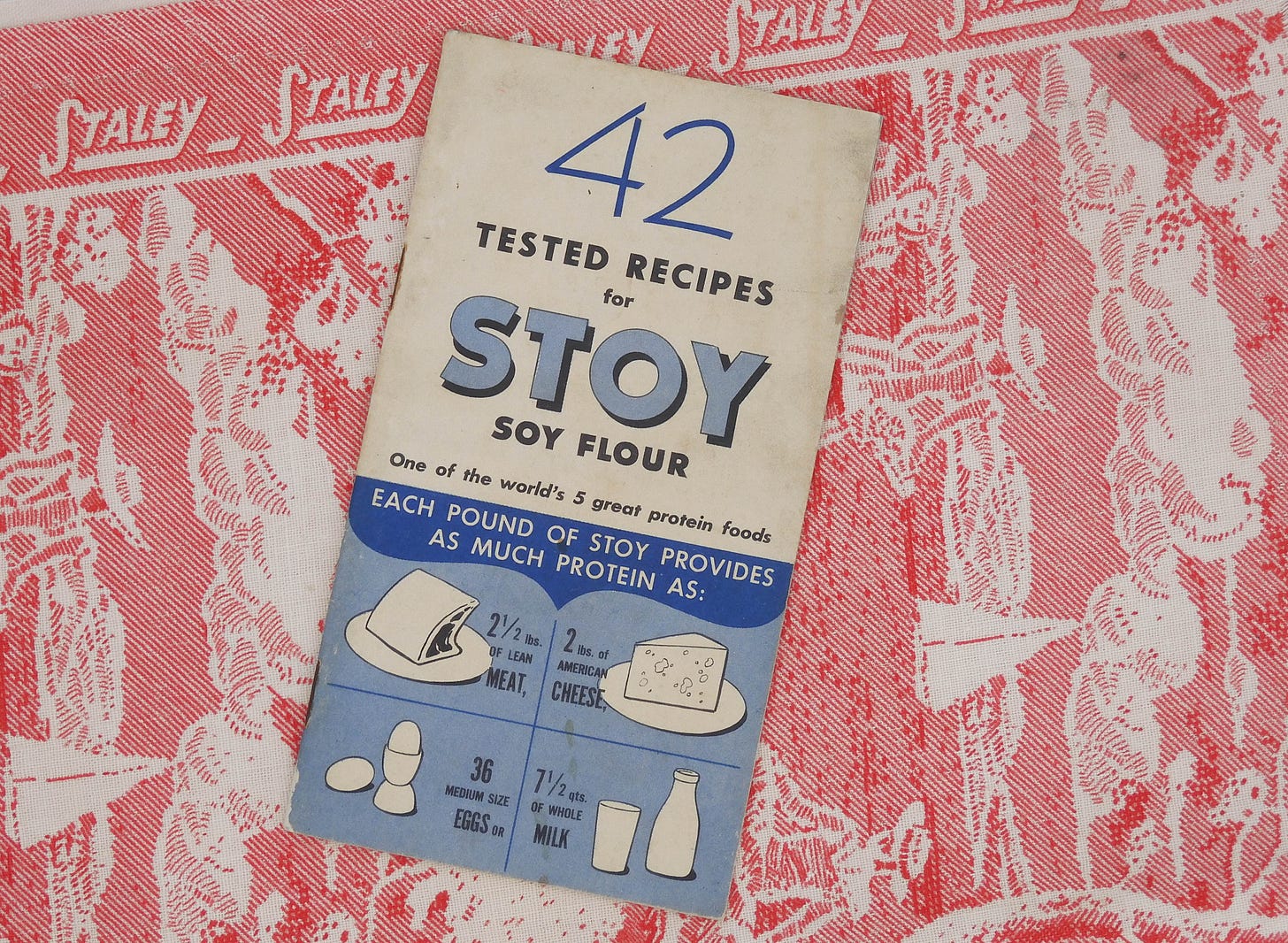

Responding to rationing on the home front, Staley packaged a soy flour, Stoy, to make up for shortages of wheat flour.

Trying to unravel the mystery of the Staley feed sack, I read through nearly every company newsletter to learn more about Stoy. A community unto itself, Staley produced The Staley Journal once a month; its editorial content sought to foster corporate culture and keep employees informed about product development. Readers could expect articles about the nutritional value of corn and soy products, production innovations, or preserving backyard harvests. Each issue featured columns of employee news – marriages, enlistments, who was ill, who was visiting on leave, scores for the softball and bowling teams. After the war began, coverage about Stoy was included in nearly every issue and highlighted efforts to market soy flour to commercial and homebakers.

In one issue, I read a notice about an executive at a Georgia textile mill producing bags for Staley, which seemed to be a promising lead. Perhaps the pretty feed sacks were produced as packaging for Stoy. The sacks are large enough for 50- and 100-pound weights of flour.

After reading dozens of Journal editions, what stuck out was what was missing. Stoy was packaged for the home market in 3-pound boxes; I found no mention of packaging used for the larger quantities required by commercial bakers. There was not a single mention or photograph of print feed sacks. Staley employed a large sales and marketing force; knowing that other processers capitalized on the use of print feed sacks, it seemed odd that A.E. Staley did not do likewise.

And yet… the logo on the feed sack selvedge matched the graphics used on other Staley products.

Another clue to the feed sack origins popped up in Feed sack fashion in South Louisiana, 1949-1968, a dissertation written by Jennifer Lynn Banning in 2005. In it, she quoted research by L. Connolly: “Staley Milling Company of Kansas City, Missouri offered Tint-sax pastel colored bags for poultry feed, corn, and stock feed,” and traced the manufacture of those bags to Percy Kent Bag Company. My bags do not have a Percy Kent logo, but it appeared worthwhile to pursue the lead.

Among the first internet search hits that came up for Staley Milling Company was A.E. Staley Mfg. Co. v. Staley Milling Co.

Filed on March 13, 1958 in the 7th Circuit Appellate Court, the case, with A.E. Staley as the Plaintiff, alleged trademark infringement. A lower court had ruled in favor of the Decatur company; Defendant Staley Milling Company, owned by J.H. Staley (no relation), appealed the lower court’s decision. The appellate court judges noted the number of years each company had been using the name – A.E. Staley Manufacturing beginning in 1912 versus Staley Milling in 1925 -- and design features similar in both company’s logos. Furthermore, the court cited issues of intent to confuse or deceive consumers about the product being sold, suggesting that Staley Milling had sought to align its product with that of the older company by using similar labeling and advertising.

In the end, the appellate court upheld the decision of the lower district court. A.E. Staley won the appeal and Staley Milling was obliged to change its packaging and marketing. Evidence of trademark infringement presented at trial still exists and can be found at auctions, in antique malls, and museum exhibits.

Records from the lawsuit seem to answer the mystery, although not as I had hoped.

Based on the available evidence, I have to conclude the feed sack was not made by or for A.E. Staley in Decatur, but for the Staley Milling Company prior to the 1958 court case. Turns out, I am one of those confused consumers the appellate court was concerned would be misled by the unauthorized use of the A. E. Staley trademark.